What’s the point of that, then? On defending the humanities in a post-PUS world.

“What do you do?” It’s a question that for many people has a straightforward answer. Of course, the unspoken suffix is “for a job”, and the fact that it’s unspoken speaks volumes about the slippage between work and self-identity. This is especially true of my profession. Being an ‘academic’ seems as much a description of my innate sensibility as it does a description of how I pay the bills.

I’m lucky enough to love what I do (casualisation, unpaid emotional labour, and pensions crises aside), but whenever someone asks me what I do I find myself preparing to defend my career. Should I give the short answer? the long answer? the easy answer? I often find myself going for the latter because it’s sometimes easier to describe myself as a ’teacher’ (a much more familiar concept for most people) than to get into the details of university lectures, seminars, and research. This is especially true for those who have little experience of higher education, where the ivory tower seems unapproachable and self-indulgent. What is it you lecturers do all day? Isn’t it nice to get such a long summer break? You must enjoy all those holidays. This is an enduring misconception and one that teachers of all kinds will recognise. When the students are off, we will still be working. It might be marking, prepping classes, writing lectures, doing outreach, or going to conferences, but often the university ‘holidays’ are the times when we do the research that keeps us at the top of our field and gets those all important REF scores.

But when I talk about my research I am also primed for what invariably comes next: what’s the point of that then? We live in a society where ‘science’ holds a kind of universally accepted innate value (regardless of its actual contributions to society), while the humanities, or anything approximating them, are generally disciplines that must prove themselves. You would never ask a biologist to justify their profession, but for some reason I often find myself being asked to do exactly that.

But when I talk about my research I am also primed for what invariably comes next: what’s the point of that then? We live in a society where ‘science’ holds a kind of universally accepted innate value (regardless of its actual contributions to society), while the humanities, or anything approximating them, are generally disciplines that must prove themselves. You would never ask a biologist to justify their profession, but for some reason I often find myself being asked to do exactly that.

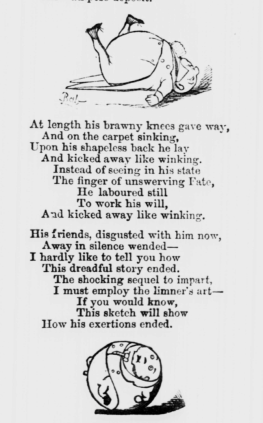

I’m a postdoc on a fabulous research project, so my teaching at the moment is light and largely voluntary. Most of my time is spent writing a book about gastrointestinal health in the nineteenth century from an interdisciplinary perspective. I look at changing understandings of digestion and digestive illness in the wider context of nineteenth century literature and culture (a time when the boundaries between disciplines were much less defined). This means that I explore developments in gastric biology, case studies from doctors, and interventions in patent or commercial medicine, alongside popular understandings that come from newspaper articles, opinion pieces, novels, poems, and satirical cartoons. Our understandings of science are rarely pure, but rather they are modified by our education, experiences, existing knowledge base, ideological belief systems, media narratives, and the sources from which we get our information.

In 2009, Dr Alice Bell described the emergence of a Post-PUS (public understanding of science) landscape, in which science talks ‘with’, not ‘at’ its publics.1 This is largely a result of the ‘digital revolution’, where information is available with an unprecedented immediacy. How many times have you been in a conversation where someone has said, “I don’t know. Google it.” And this you can do from your smartphone – the answer to almost any question is literally at our fingertips. The comment boxes at the bottom of articles enable people to engage with science in new ways, to take part in the discourses of science and forge their own narratives on social media, blogging sites, and via the “retweet” feature.

The Penny Illustrated Paper and Illustrated Times (31 Dec 1892)

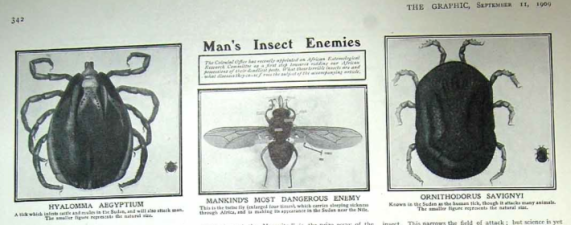

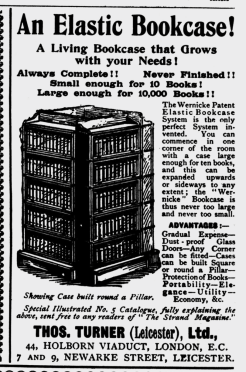

This is in fact not a new phenomenon. Cheap mass publishing formats and emerging mass literacy in the nineteenth century facilitated a huge change in access to information for the general public. The periodical press, with its wealth of cross-disciplinary material enabled individuals to read fiction alongside scientific essays, to enjoy poems about the telegraph, alongside advertisements for everything from electropathic belts to expanding bookcases! And oftentimes readers would write in with their questions and stories. Some would carry out self experiments and regale other readers with their findings. The anecdotes of people who had given up cheese or potatoes for a week for example contributed to public dietetic knowledge just as much as doctors’ recommendations or patent advertisements did. Sydney Whiting’s hugely popular mid-century novel Memoirs of a Stomach (1853), which followed the life-story of the personified, ‘Mr Stomach’, was for many people a key source of information about digestive health.

As scientific knowledge travels through new mediums, it takes on new meanings, as I’ve written about elsewhere.2 Even organisation likes the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention have used new mediums to communicate with their readership in meaningful ways, such as when the CDC produced a “Zombie Preparedness Campaign” which included a graphic novel. This incredibly effective campaign used the cultural symbol of the zombie as a way of thinking about viral pandemics and natural disasters as situations that cause mass hysteria, panic, and secondary dangers from infection and the collapse of infrastructure. Ironically, the public found the idea of a Zombie apocalypse a much more relatable idea than a natural disaster, and it was certainly an illustrative one.

Curiosity Carnival 2017 photograph by Ian Wallman

My first degree was in biology, and I tend towards empiricism. However, literary and autobiographical narratives can tell us things, about experiences of pain for example, that physiological and neurological knowledge alone cannot. I’ve personally learnt a lot about my physical and emotional self through learning how to dance. I once heard my dance teacher say “I know my body” and it stuck with me because she is engaged with and listening to her physiology in ways that are very different to—and I would suggest—a lot more meaningful than might be achieved by studying an X-ray or MRI scan. Work by scholars like Susan Sontag and Charles Rosenberg (and many others besides) have shown us how the language and metaphors we use to talk about disease (the ‘war’ on cancer, she ‘lost her battle’) can radically affect a patient’s experience of illness.3

It is not to devalue science to recognise that it is not the only form of knowledge that has value. If we really do live in a post-PUS world then the humanities has much to offer. They can help us navigate and engage meaningfully with the wealth of information available (#fakenews #posttruth). They can teach us how to interrogate the framing narratives that accompany science and also form deeper understandings of it. And the humanities can help practitioners understand their patients in new ways (even decoding the way a patient reports their symptoms—usually as a linear narrative—can be an exercise in what literary scholars call ‘close reading’).

For myself, I hope my research might shed light on ‘new’ understandings of the body informed by recent developments in the field of microbiome studies. Science and humanities are best when they work with, not against each other. As this humorous poster from the University of Utah jokes: ‘science can tell us how to clone a t-rex, humanities can tell us why that might not be a good idea.’

1 Alice Bell, ‘Doing it by the Book: Introductory Guides for Twenty-First Century Science Communication’ Science as Culture 18.4 (Dec 2009) pp.511-514. (p.512).

2 Emilie Taylor-Brown, ‘Death, Disease, and Discontent: The Monstrous Reign of the Supervirus’ in Unnatural Reproductions and Monstrosity: the Birth of the Monster in Literature, Media, and Film eds. Andrea Wood and Brandy Schillace (Amherst: Cambria Press, 2014)

3 See: Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and its Metaphors (London: Penguin, 2009)

Charles Rosenberg and Janet Golden eds. Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992)

Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985)

And while you’re at it, check out:

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003)

From: L. F. Austin and A. R. Ropes, ‘The Whirligig of Time’ The English Illustrated Magazine 123 (Dec 1893) pp.261-68.

From: L. F. Austin and A. R. Ropes, ‘The Whirligig of Time’ The English Illustrated Magazine 123 (Dec 1893) pp.261-68.

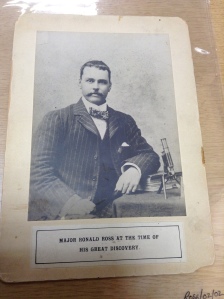

Despite this divisive rhetoric and petty name-calling—like when Dr. T. Edmundston Charles called Italian researcher Giovanni Battista Grassi a “ten horse-power donkey”5—the progression of tropical medical science was a global affair, which relied on global collaboration.

Despite this divisive rhetoric and petty name-calling—like when Dr. T. Edmundston Charles called Italian researcher Giovanni Battista Grassi a “ten horse-power donkey”5—the progression of tropical medical science was a global affair, which relied on global collaboration.

asis).

asis).