Top Doctors & Police Psychics: A Victorian Legacy.

[Photo Source: http://greghouse.weebly.com/house-and-holmes.html%5D

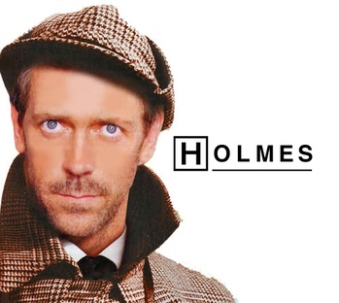

I had a conversation recently with a friend and colleague about Victorian legacies. Whether subtle or overt, echoes of the nineteenth century are found everywhere in the twenty-first. The contemporary penchant for Victorian adaptations, Dickensian-inspired dramas and facsimile Victoriana reflects the modern obsession with a time rich in cultural intrigue. But some of these engagements are less conspicuous, elegantly paying homage to the era, all the while maintaining a separate and complex identity. One such example is the celebrated American television show, House. This 8 season medical drama takes its premise from Conan Doyle’s famous literary detective, paying homage to Sherlock Holmes with the programme’s title character. His kindred sidekick Dr John Watson is reimagined as Oncologist Dr James Wilson, continuing the ‘true friend’ motif and position as some-time flatmate. Watson’s psychosomatic leg pain is transferred to House and made a very real injury, which provides the basis for his addiction to the painkiller Vicodin (parallels here with Holmes’ Cocaine use). Holmes’ distaste for people and awkward social skills are inflated to almost sociopathic levels, underscored by his love of puzzles. His musical talent is upheld, exchanging the violin for the dulcet tones of the piano and the more rock and roll appeal of the electric guitar. The iconic pipe is usurped by a now equally iconic cane, and the deerstalker replaced variously with a backwards baseball cap and motorcycle helmet.

Interestingly, the programme inverts the protagonist’s occupation, paying homage to its original inspiration. In a voice recording held at the British Library, Doyle credits his conception of Holmes to his Edinburgh medical mentor’s ‘great powers of observation’. Noting the prominence of detection in scientific inquiry and the absence of methodology in detective fiction, he decided to combine the two, successfully reinventing the figure of the detective as an enlightened and starkly scientific icon: ‘…the hero would treat crime as Dr. Bell treated disease, and science would take the place of chance.’[1] Thus Holmes’ was to treat crime as disease, in the same way that House treats disease as crime. House’s patient histories are more like witness statements, searching their homes for clues and interrogating their alibies with the supposition (and show’s tagline) that ‘everybody lies’.

Further parallels might be drawn between Holmes’ rocky relationship with the police and his interactions with Princeton Plainsboro’s Dean of Medicine. His position as ‘consulting detective’ could almost replace ‘head of diagnostics’ on House’s office door. This hired-out consultancy puts me in mind of another US television show, The Mentalist. Returning to the realms of solving crime, Patrick Jayne is an independent consultant to the fictional California Bureau of Investigation. Jayne’s powers of deduction are exaggerated to the point of psychic powers, the extent of which is never fully ascertained. This might be interpreted as a reference to Doyle’s later interest in spiritualism.[2] Nevertheless, a rational explanation accompanies Jayne’s apparent mind-reading, the suggestion being that he is an incredibly intuitive reader of body language and like Holmes’ reads people and situations like a doctor might read symptoms. The eponymous Sherlockian figure ‘Professor Moriaty’ might even be found in Jayne’s archenemy ‘Red John’, a serial killer with intelligence and cunning to rival Doyle’s criminal mastermind. However, Jayne’s character is softened by his subversive charisma, and the replacement of cold truth-chasing for a personal vendetta (Red John killed Jayne’s wife and daughter five years before the setting of the show).

These brief examples go some way to exposing the wealth of historical literary engagement in the twenty-first century and the ingenuity of classic adaptations retuned for modern audiences. Engagement with the cultural products of the nineteenth century continue to find new and diverse forms, and Victorian legacies persevere with meaningful poignancy. If this teaches us anything, it’s that a well-written narrative, regardless of cultural context, really is, timeless.

[1] A. Conan Doyle, Early Spoken Word Recordings (1930) Published online by the British Library; available at: <http://sounds.bl.uk/Oral-history/Early-spoken-word-recordings/024M-1CL0013693XX-0100V0>

[2] David Oldman, Spiritualism. Arthur Conan Doyle: An Online Exhibit published online by City of Westminster Libraries at: <http://www.westminsteronline.org/conandoyle/Spiritualism.html>